JILL WIGGINS|GUEST

Earlier this month, I witnessed the assault on our nation’s Capitol with incredulity. In the aftermath, I found myself consuming copious amounts of media examining responses from political leaders, pastors, and news sources. It did not take long before a myriad of politicians from both parties adopted the familiar phrase often uttered by parents and teachers alike to children whose behavior has been disappointing— “We are better than this.” Although I understand the sentiment and its guilt-eliciting, behavior-changing appeal, I would respectfully and broken heartedly disagree with their proclamation. We as Christians should be the first to point out that “we are not better than this.”

I spent the better part of my teenage years thinking that I was “better than this.” I grew up in a small Baptist church in northeast Alabama and our offering envelopes came preprinted on the front with a variety of boxes to check. There was a box for attendance, daily bible reading, offering, and lesson preparation. Every Sunday night at youth group, my goal was to very literally turn in an envelope that checked all the boxes, because along with not drinking, smoking, cussing, or fooling around with boys, that was what “Good Christians” did. In the years since, the list has become more political in nature, but the sentiment is the same. Then and now, there are boxes to check, issues to support, causes to champion. These are things that Christians do. . . and those are things Christians do not do. Though not overtly stated, I perceived that there was “us” and there was “them.” We were good “box-checking” Christians, and “they” were dirty, bad, vile, worldly, sinners.

Yet, one Sunday night, the summer following my senior year of high school, I found myself face down on the hook rug on the floor of my bedroom, crying out to God. I realized that I was one of “them.” I was dirty, bad, vile, and worldly. For all my box checking, I was a fraud. A pit formed in my stomach, and I believed that if everyone knew just how really bad I was, how dirty I felt on the inside, no one would ever love me. And that’s when I met Jesus. After all, we must first see the sin in ourselves to grasp the wonder of God’s grace.

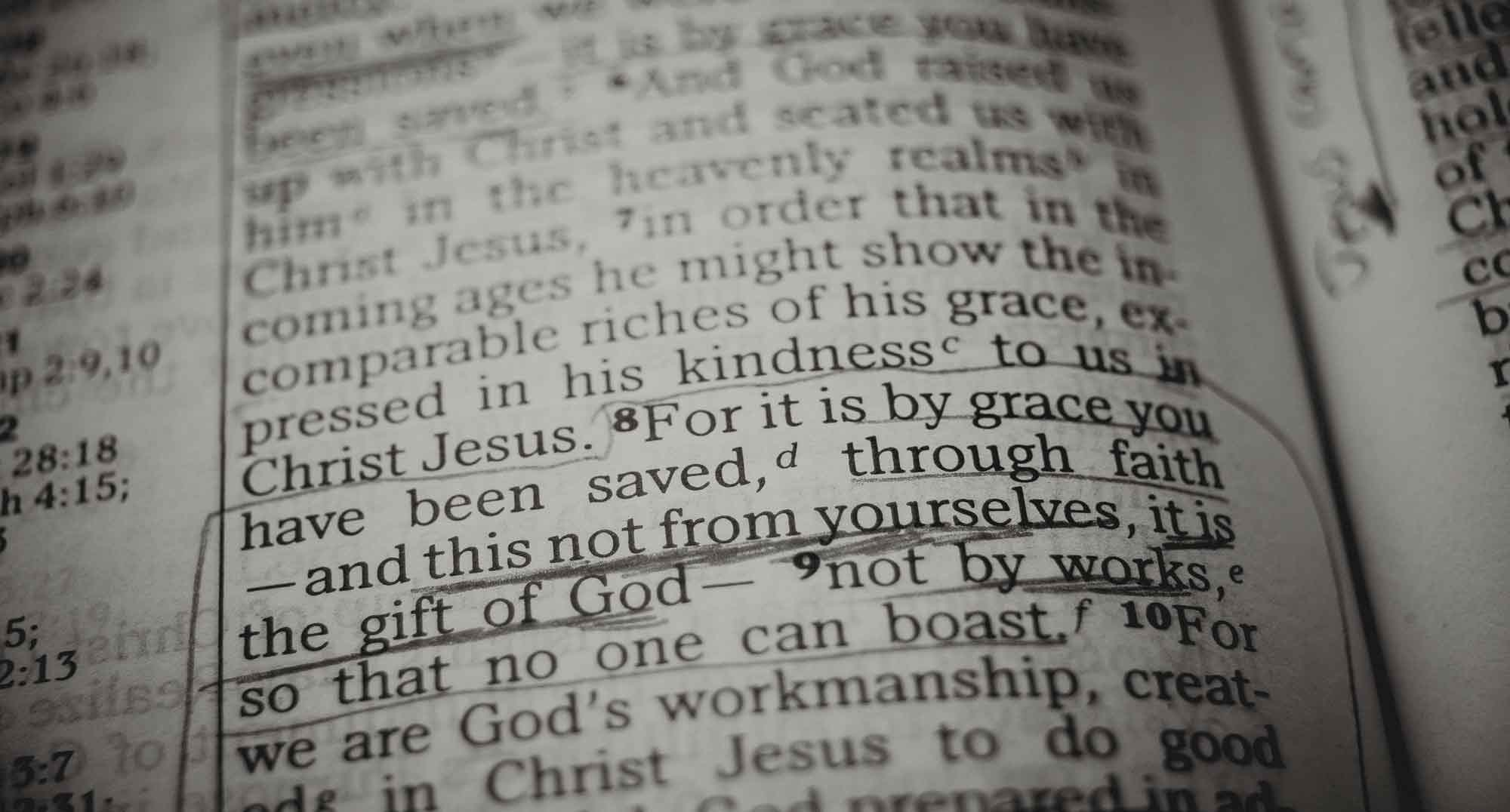

Paul in his letter to Timothy states that “Christ came into the world to save sinners of whom I am foremost” (1 Tim. 1:15). Present tense. Jesus came into the world to save sinners like me. Sinners. Like me. And that is the good news. That is the gospel. That is grace.

When we as Christians are the first to acknowledge our own sin, we tear down the walls separating “us” from “them.” We confess that we are all sinners in desperate need of a savior. We confess that in ourselves there is no good thing— that our righteousness, the futile attempts to check all of the boxes, is like filthy rags— and that apart from God we can do nothing. Experiencing the transformative power of the gospel demands we first acknowledge our own sin, our total depravity. We acknowledge the natural condition of our hearts and concede that without God’s grace and the restraining power of the Holy Spirit, we are not “better than this.”

After all, Peter was not better than denying Christ to a servant girl in the wake of Christ’s arrest. David was not better than sleeping with another man’s wife and committing murder to cover it up. Moses was not better than murdering an Egyptian and smashing God’s word in a fit of rage, and Abraham was not better than pretending his wife was his sister to save his own skin. If the Rock on whom Jesus would build his church, a man after God’s own heart, the writer of the Pentateuch, and the father of Israel are not “better than this,” then I certainly am not either. When writing TULIP and Reformed Theology: Perseverance of the Saints, for Ligonier Ministries, R. C. Sproul acknowledged that apart from God’s grace, our own attempts to be good enough in our own strength and volition will fall short. “The apostle Paul warns us against having a puffed-up view of our own spiritual strength. He says, ‘Therefore let anyone who thinks that he stands take heed lest he fall’ (1 Cor. 10:12 ).”[1] Stated differently, before we can appreciate the gospel, the transforming power of God’s grace, we must first concede that in ourselves we are powerless to be “better than this.”

Christians saved by God’s grace should recognize ourselves in the worst our nation has to offer. We should see ourselves in the faces of those storming the Capitol, demanding our rights, our way. We should see ourselves in the arrogance of the police officer with his knee on the neck of the oppressed, drunk with power. We should see ourselves in politicians and news channel personas, calling names, pointing the fingers, maligning others, casting blame, and spewing poisonous venom of political discourse— and we should see ourselves in the voices of another angry mob demanding the release of Barabbas and the crucifixion of Christ. Only by confessing our natural bend to sin and the acceptance God’s irresistible grace can we lift our voice with that of the thief asking a dying Jesus for rescue and forgiveness.

Oh Lord, forgive us. We confess to You that we are not better than this.

[1] Sproul, R.C. “TULIP and Reformed Theology: Total Depravity.” Ligonier Ministries, 25 Mar. 2017, www.ligonier.org/blog/tulip-and-reformed-theology-total-depravity/.

About the Author:

Jill Wiggins

Jill Wiggins received her MA in English from Georgia State University and is a 7th grade English teacher. She and her husband John have been married for 25 years and have three children, the oldest of whom is a nineteen-year-old with autism. They attend Briarwood Presbyterian Church where they are active in the Special Connections Ministry and also serve on the Young Life Committee for Birmingham South. You can find her on Twitter @jillwiggins.